The Furnace Keeper of Delancey Street

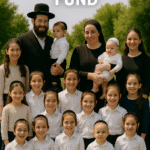

The year was 1892. The air in New York City was thick with the smoke of industry and the scent of hope. Ships arrived daily at Ellis Island, carrying souls from across the ocean—dreamers, refugees, and survivors. Among them was Reb Mendel, a Hasidic Jew from a small shtetl near Minsk, clutching the hands of his twelve children as they stepped onto American soil. His beard was long and silvered, his peyos curled tightly, and his eyes—though weary—burned with the fire of unwavering faith.

They had fled the pogroms, the hunger, the fear. In Russia, Mendel had been a melamed, a teacher of Torah. But in America, Torah didn’t pay the rent. The Lower East Side was teeming with immigrants, and jobs were scarce. Every factory, every shop, every warehouse demanded six days of labor—and the seventh, the holy Shabbos, was no exception.

Mendel refused. “Better to starve with dignity,” he told his wife Chana, “than to eat bread baked in the fire of chillul Shabbos.”

Weeks passed. The children grew thin. Their shoes wore through. Then, a building superintendent offered Mendel a job: stoking the coal furnace of a tenement on Delancey Street. It was brutal work—shoveling coal into the roaring belly of the furnace day and night—but it didn’t violate Shabbos. And so, he accepted.

The family was given a place to live: the cellar, just feet from the furnace. It was dark, damp, and suffocating. Soot clung to every surface. The children’s skin, once pale from the Russian winter, turned black with coal dust. Their hair matted, their clothes stained. But they sang. They played. They spoke Yiddish with joy and innocence, their voices echoing through the alleyways like forgotten prayers.

One afternoon, a well-dressed woman named Mrs. Esther Rosenfeld walked past the building. She was the wife of a wealthy factory owner, and she was on her way to a charity luncheon. As she passed the alley, she stopped in shock. A group of Black children were playing jacks on the sidewalk, laughing and chattering—in fluent Yiddish.

She blinked. Surely she was mistaken. She approached them, and one of the boys looked up and said, “Gut morgen, froy.”

Esther’s heart skipped. She had never seen Black children speak Yiddish. She followed them to the cellar door and knocked.

Rebbetzin Chana opened it, her face streaked with soot, her eyes tired but kind. Esther stepped inside and gasped. The room was barely lit. The walls were black. A single cot was shared by three children. And yet, on the table sat a worn Chumash and a pair of Shabbos candlesticks.

Chana told her everything. The escape from Russia. The refusal to work on Shabbos. The furnace. The soot. The hunger.

Esther wept. “My husband owns a factory in Brooklyn,” she said. “We can offer your husband a job. A real job. And a proper home.”

That evening, the Rosenfelds returned with a contract and a check. “You’ll have Sundays off,” Mr. Rosenfeld assured Mendel. “You won’t have to work on Shabbos.”

Mendel looked at the paper, then at the check. It was more money than he had ever seen. But he asked one question: “Does the factory operate on Shabbos?”

“Yes,” Mr. Rosenfeld admitted. “But you won’t be there.”

Mendel shook his head. “I cannot accept money earned through chillul Shabbos. Even if I do not work, the factory does. That money is tainted.”

Mr. Rosenfeld was speechless. “You would rather live in soot and hunger than take honest work?”

“It is not honest,” Mendel replied. “Not for me.”

That night, Esther and her husband sat in silence. They had met many men in business—clever men, ruthless men, desperate men. But never a man like Mendel.

The next morning, Mr. Rosenfeld made a decision. He would open a new division of his factory—one that operated only six days a week. No Shabbos. No compromise. He offered Mendel the position of supervisor, and a home in Williamsburg.

Mendel accepted. The family moved into a modest apartment with windows, light, and clean air. The children bathed, their skin returned to its natural hue, and they began school. On Friday nights, their home glowed with the warmth of Shabbos candles, and the songs of joy and gratitude filled the air.

Years later, the Shomer Shabbos division of Rosenfeld Textiles became a beacon for Orthodox Jews seeking work without sacrificing their faith. And Reb Mendel, the furnace keeper of Delancey Street, became a legend—not for his suffering, but for his strength.

Takeaway:

The story of “The Furnace Keeper of Delancey Street” is a powerful testament to the strength of personal integrity and unwavering faith. Reb Mendel’s refusal to compromise his religious convictions, even in the face of poverty and hardship, ultimately inspired respect and meaningful change. His steadfastness not only preserved his family’s dignity but also led to the creation of new opportunities for others who shared his values. The narrative demonstrates that true courage is found in holding fast to one’s principles, and that such determination can have a lasting, positive impact far beyond one’s own life. The story of Mendel also reflects Parshas Bereishis, where Adam is cursed to toil for a living, and the sanctity of Shabbos is mentioned. By refusing work connected to Shabbos desecration, Mendel shows that honoring Shabbos elevates our labor and gives dignity to our lives, turning hardship into spiritual strength.